The Cross-Sector Collaboration Task Force meeting on Tuesday, July 25th at Luke C. Moore High School focused on D.C.’s complicated lottery and what an “at risk” preference is. The task force working group on improving outcomes for at-risk students hosted an informative presentation by Cat Peretti, Executive Director of the My School DC Lottery, on the possibility of including an at-risk preference in the city’s random, cross-sector school admissions lottery. Peretti answered questions from task force members, explained the technical details of lottery preferences, and discussed how such a policy would affect different school populations.

What is an At-Risk Preference?

An at-risk preference would help students deemed “at-risk of academic failure” gain access to their preferred schools through the city’s random admissions lottery. DC Code sets the definition for at-risk as anyone who is homeless, in the foster care system, qualifies for TANF or SNAP, or is an over-age high school student. My School DC assigns a random number to all applicants who enter the lottery, but those who qualify for particular preferences may jump in line based on particular criteria set by each school. Examples of preferences include a sibling preference, an in-boundary preference for families applying to their neighborhood DCPS school, a transfer preference for those moving from one campus to another within the same charter network, and a children of staff preference for employees of certain charter schools. Children who qualify for a preference are offered space in a school before those who don’t qualify for one. 38% of matches in the 2015-16 lottery were for applicants with a preference.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sx7-o-ff9y4&feature=youtu.be

An At-risk Preference was proposed (and Controversial) Before

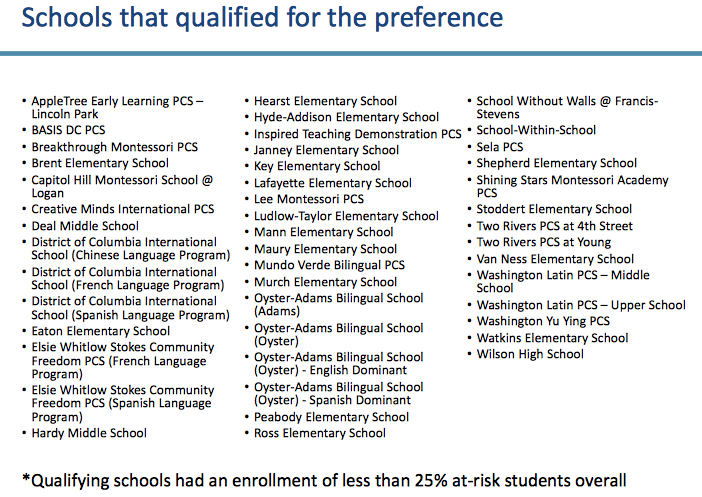

The DC Advisory Committee on Student Assignment, convened by Mayor Vincent Gray in 2013-14, recommended that all DCPS and charter schools with less than 25% at-risk student bodies prioritize at-risk students in the lottery. This recommendation caused representatives of the Public Charter School Board to resign from the committee and write a letter saying in part, “We would like to request that the recommendations of the committee not include specific recommendations of any preferences – mandatory or voluntary – with respect to charter schools”. Charter board leaders felt that the proposal needed more analysis, that a “clean” lottery would be preferable, and that the committee’s lack of charter school representatives made it ill qualified to make such a recommendation.

Different Versions of the Preference Showed Varying Effects

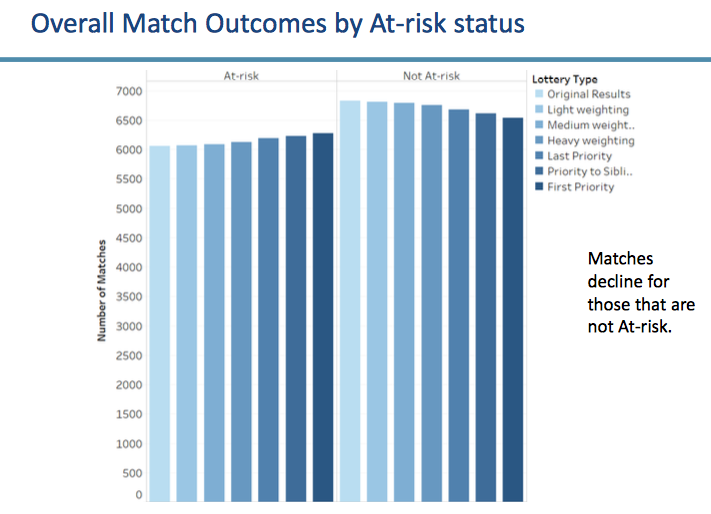

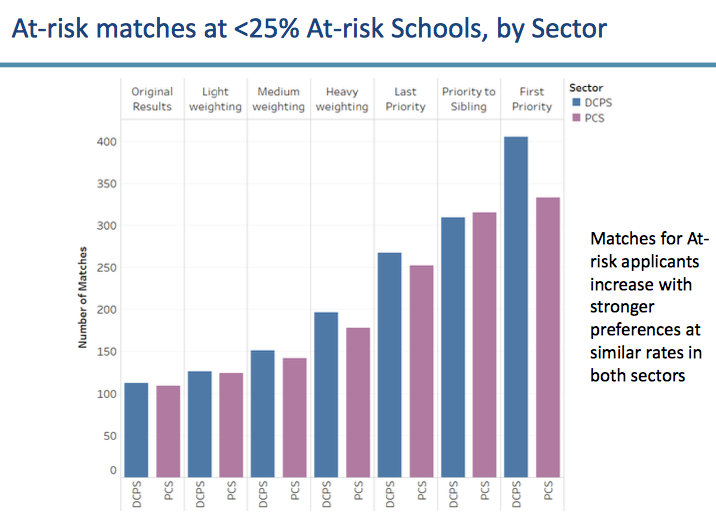

The strength of an at-risk preference comes down to how it is implemented. The My School DC team ran six different scenarios: three versions of a “weight” preference that would move an at-risk student up within his or her preference group and three versions of a “priority” preference which would allow at-risk students to jump ahead of other groups. The weight options (light, medium, and high) generally had less of an effect than priority options because, for example, applicants with an in-boundary preference to DCPS neighborhood schools would retain first access before those living out of boundary. The three priority options gave increasingly preferred status to the at-risk student group, from last priority up to first priority, in which their status as at-risk would trump all other preferences including neighborhood and sibling. As evidenced by the charts below, overall match rates for students not labeled at-risk would decline under each version of an at-risk preference.

Questions and Concerns Remain

Participants expressed concerns that such a proposal could provoke backlash and unintended consequences. Under the strongest first priority option, 610 at-risk applicants would receive a better or new match, but 565 not at-risk applicants would lose or get a worse match. Under such a proposal, an at-risk student applying to Janney Elementary School, a DCPS neighborhood school in the affluent upper-Northwest neighborhood of Tenleytown, would have greater opportunity to gain access to the school’s coveted PK-4 seats than a student living in-boundary or with a sibling already attending the school. Several task force members also expressed concerns that schools without large at-risk student populations may lack sufficient mental health staff to support the needs of at-risk students, and thus resort to exclusionary discipline tactics like suspension or expulsion. Technical concerns over identifying at-risk PK3 applicants also remain, though this data may be available from other government records.

The next Cross-Sector Collaboration Task Force meeting is scheduled for Tuesday, October 24th, 2017, at the KIPP DC Webb campus (1375 Mt Olivet Rd NE) from 6:00 to 8:00pm. Further information can also be found at https://dme.dc.gov/collaboration.

No Comments